This project—to document the 32nd Station Hospital and the men and women who served with it—began in earnest in the summer of 2018. Its origins, however, stretch back some years. At the time of this writing in May 2019, I’ve contacted about 60 families of 32nd Station Hospital servicemembers. My phone calls, letters, or Ancestry.com messages come out of the blue, so they are often met with curiosity about the nature of and inspiration for the project.

I grew up in Rockville, Maryland. Even as a child, I had a strong interest in history, particularly that of World War II. On the other hand, I had less interest in family history, particularly my paternal grandparents, Robert and Lucille Silverman, who died before I was born.

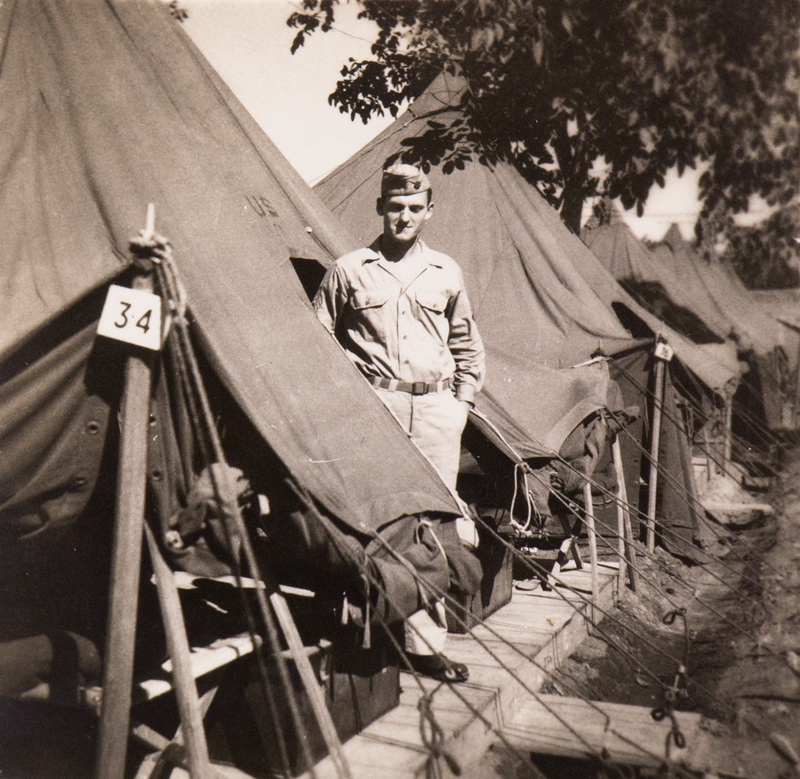

I was in high school back when I first became curious about the 32nd Station Hospital. Undoubtedly it was a result of looking through my grandfather’s scrapbook, housed in the Silverman Family Archives (aka the buffet in our dining room). Around the summer of 2001 (possibly inspired by a family history project that school assigned my class), I searched for information about the 32nd Station Hospital on the internet, and discovered Willard O. Havemeier’s website.

Although our correspondence is now lost (with the closure of the family America Online account!), I recall reaching out to Havemeier. Havemeier—who had been an N.C.O. assigned to the 32nd Station Hospital’s Registrar Office—knew my grandfather, though not particularly well since they were in separate sections and because officers and enlisted men didn’t socialize together.

Havemeier lived in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, just over two hours’ drive from where I lived. My parents and I met Havemeier and his wife (I think it was twice) in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, which was roughly midway between us. He gave us a handful of photocopies of materials related to the 32nd Station Hospital. I can’t recall if we gave him copies of any materials from my grandfather’s scrapbook or 8 mm film, but if we did, they didn’t end up on his website.

Havemeier also gave me the phone number for Dr. Louis Linn, who was a friend of my grandfather’s. They served together in the 32nd Station Hospital stateside and in Tlemcen, Algeria until Dr. Linn was transferred to another unit in mid-1943. I had a phone conversation with Dr. Linn sometime around the fall or winter of 2001-2002. Unlike the Havemeier correspondence, I do have notes from the phone call with Dr. Linn. He suggested I try to contact Dr. Irving Weiner, another friend of my grandfather’s from the unit. (As it turned out, Dr. Weiner had died in the summer of 2001, but his extensive collection would prove valuable to this project years later after I contacted his daughter.)

As far as I recall, I did not research the 32nd Station Hospital any further while I was in high school. At the time, I guess I really didn’t have the attention span or research skills to move further, although I have lingering regrets that I didn’t try harder to speak with more members of the unit while they were still alive. I suppose it was also likely that I considered Havemeier’s work to be all that was necessary to properly document the 32nd Station Hospital’s story. At any rate, I lost touch with Havemeier around the time that I left for college in the fall of 2002.

While in college, although majoring in history, I developed an interest in emergency services. I graduated from the University of Delaware in 2006, but couldn’t really picture myself working as either a historian or history teacher. Instead, I became a fulltime 911 dispatcher immediately after graduation. The following year, I joined my local fire department, serving as an emergency medical technician, volunteer firefighter, and eventually as a C.P.R. instructor.

During a visit back to Rockville in May 2015, I decided to take another look at my grandfather’s scrapbook and photographs. That my wedding was coming up in three months may have piqued my interest in family history again. Both my fiancée Rachel and I had decided to wear our grandparents’ watches on our wedding day. In my case, it was my grandfather’s pocket watch, a gift from my father some years earlier. It occurred to me that I didn’t know very much about my grandfather. Since his World War II photos were still sitting in an envelope, I asked my father if I could take them and put them into an acid-free album. I also thought about doing a digital restoration on a beautiful full page Don Sudlow drawing in my grandfather’s scrapbook, and asked my father to scan it.

Thanks to a series of major life events, my grandfather’s artifacts remained unexamined and in storage for a while longer. Rachel and I married in August 2015 and welcomed our first child one year later. As is always the case, parenthood proved to be a fundamental change in my life. What little free time I had was frequently spent at home when the baby was asleep. I finally began working on a restoration of the Don Sudlow drawing in the fall of 2016. But with a promotion, a move, and then news that another baby was on the way, the project stayed on the backburner for almost two more years.

Although I was initially satisfied with my work on Sudlow’s drawing, I subsequently realized that the source image that I started with was actually low resolution. In August 2018, I obtained a new high-resolution scan from my father. In addition, after I discussed my grandfather’s World War II memories with my uncle during a visit to Cape Cod that same month, he sent me Robert Silverman’s World War II wallet and records.

I spent about seven hours digitally restoring Don Sudlow’s drawing of my grandfather. As I pored over every detail of the drawing, I grew more curious about both the artist who drew it and the man it depicted. Around the same time, I began scanning my grandfather’s photographs. I figured that if I was going to put them in an album, it would make sense to scan them beforehand so they wouldn’t need to be taken out later in order to read any text on the back. I also decided to have my grandfather’s 8 mm films digitized as well.

Once I had digitized the photos and film, I wanted to know about the men and women depicted in them. Only some of the individuals were identified on the backs of the photos, and of course there were no names at all associated with the film footage. A new thought entered my mind: Wouldn’t the descendants of these men and women like to see these pictures too? Although the chances of not only identifying the individuals but also contacting their families initially seemed insurmountable, with the amount of information available on the internet these days, I thought the idea might actually be promising.

In October 2018, I made two visits to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, where I was able to scan the 32nd Station Hospital’s surviving reports. These included three different officer rosters, but virtually no names of enlisted personnel. Still, the officer rosters made it possible to identify some of the people listed on the back of the photos, even when only a partial name or nickname (“Wes” or “Vinnie“) was listed.

That same month, I was looking for information about Flight Sergeant Eric Ramsay (R.A.F.V.R.). Ramsay, who was killed in action during the closing months of the war, was a good friend of my other (maternal) grandfather, a radar operator in the U.S. Army Air Forces. I was surprised to find that somebody had created a website about Ramsay’s unit, the 75 (NZ) Squadron. The site had an incredible level of detail, listing details of each of the unit’s operations, both in terms of the squadron as a whole as well as each individual crew. I contacted Simon Sommerville, the website’s creator, to share photos and letters with him regarding Flight Sergeant Ramsay. Sommerville mentioned that he had collected a great deal of material from people who had found his website. His ultimate goal was to create a “Nominal Roll” listing all flight crew who served in the squadron.

Originally I had planned to write a few posts about my grandfather’s journey and Don Sudlow’s cartoon’s for my existing website. That blog, which I started in 2015, was focused on travel, with the occasional history post. Up until I corresponded with Sommerville, it had never really occurred to me that I could create my own website about the 32nd Station Hospital. Although Willard Havemeier’s website was quite impressive for its time (heck, my grandmother is from his generation and she never even learned to use email!), it was limited in many ways. The images were low-resolution, since his website was developed during the pre-broadband era. The content was also naturally focused on Havemeier’s own experiences, with only a couple of letters included from other members of the unit.

Instead, inspired by Sommerville’s example, I decided to create an entirely new website about the 32nd Station Hospital, with the goal of covering the unit’s history more comprehensively than Havemeier had. The Nominal Roll that Sommerville mentioned subsequently became the inspiration for an even more ambitious part of my own project, the Personnel section. That part of my site evolved to have the lofty goal of eventually listing not only the names, but also the photographs and short biographies of every known member of the hospital unit.

On November 2, 2018, I examined part of the Dwight McNelly and Dorothy Eggers Collection at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library in Chicago. The main objective of the trip was to examine photographs of the dud bombs that nearly devastated the 32nd Station Hospital during the air raid on April 24, 1944. However, I was also able to view and photograph two drafts of McNelly’s unpublished manuscript and obtain a list of 32nd Station Hospital survivors dated 1994. Both would prove quite valuable for the project.

This website went online November 7, 2018. Soon after, I decided to join Ancestry.com with a trial membership and see what I could find out about the members of the 32nd Station Hospital. I also realized that Ancestry might prove useful for both identifying the people in his photographs as well as sharing them with any descendants they might have.

Ancestry indeed proved invaluable for the project. In fact, of the approximately 60 families of 32nd Station Hospital members that I’ve successfully contacted so far, Ancestry played a role in locating about 35. Many of the rest were located through searches on Whitepages.com with names located through articles found in historic newspapers through Newspapers.com or obituaries located with Google.

The project’s progress has resembled a branching web. As I contact new families, I sometimes obtain new photographs and documents. Sometimes these items reveal a new name, address, or other new lead that helps me contact a different family. As of May 2019, this website already contains material contributed by 22 different families. In the long run, I hope that other families will stumble across my website and get in touch (something that has happened twice so far).

What this project has achieved exceeded my wildest expectations. Some of my proudest moments so far include:

- I identified a celebration featured in about 2 minutes of my grandfather’s 8 mm footage as being from a tea party prior to the wedding of Dr. Isadore Wessel and Florence Benichou in Algeria in 1943. I was able to share it with their children; in return I learned a new story about my grandfather and received a photo (of my grandfather with other dentists) from Dr. Wessel’s collection.

- I contacted Dr. Irving Weiner’s daughter and was able to share a photo of her father with her that she hadn’t seen before. In return, I received many items from Dr. Weiner’s collection, including a photo of him, my grandfather, and Frances Rubin posing with legendary performer Al Jolson during his visit to the hospital. Interestingly, neither Dr. Weiner’s daughter nor I recognized Jolson initially, but Rubin’s daughter did…one more example of how reaching new families has helped this project expand by leaps and bounds.

- I was able locate the children of three nurses who were best friends during the war—Ina Bean (Carey), Annie Barone (Hagerty), and Ruby Milligan (Hills)—and put them in contact with one another. Bean and Barone married officers from the unit, making five out of six of their parents affiliated with the unit. All three families have impressive collections and many of the photos I received from them are already illustrating several articles on this site. In addition, the documents from the Carey Family proved especially valuable in my research (especially a pair of lists of officers and nurses that were assigned to the unit in late 1942, prior to the earliest extant roster in the National Archives).

- I contacted the nephew of Dorothy Mowbray, who I suspected was a member of the unit. Not only was he able to confirm that she was, but he found a pair of manuscripts about her wartime experiences that he had not examined since her death decades earlier. He told me my work rekindled memories of his aunt and pride at her service.

I am happy to have been able to share photos and documents with the families of the people my grandfather served with and glad that I’ve received so much in return. At the risk of sounding pretentious, I feel that, during the course of this project, the faces in my grandfather’s photos and films have evolved from being those of strangers to something akin to old friends. It has been my honor to play a role in keeping the memory alive of these men and women, who served their patients and their country so well during long years of crisis.

Last updated October 27, 2019

Hi Lowell, I want to thank you for all the information you have made available regarding the 32nd station hospital.

I had no information as to my fathers active duty during the war. It was not something he talked about. All he ever said was that marching was hard.

I have tasked my sibling with gathering photos they may have. When complete I will forward to you.

Thank you again,

Cynthia

daughter of Ernest S. Clark

LikeLike