Killed in a plane crash on November 24, 1943, the day before Thanksgiving, 2nd Lieutenant Rachel Hannah Sheridan had the sad distinction of becoming the first of two people to die while serving with the 32nd Station Hospital during World War II. Sheridan was also only woman to enter military service from Delaware who died overseas during the war. I first learned about Rachel Sheridan from the memoir on Willard Havemeier’s website and became curious about the circumstances of her death. To my surprise, I was able to find abundant information about her. The biggest challenge, as it turned out, was separating fact from lore.

Rachel Sheridan was born in 1918 in Carbon County, Pennsylvania (various sources list Audenried or Yorktown, both near McAdoo), the fifth of seven children born to Thomas and Hannah Sheridan. Rachel had three older brothers, an older sister (who died very young), as well as a younger sister and a younger brother.

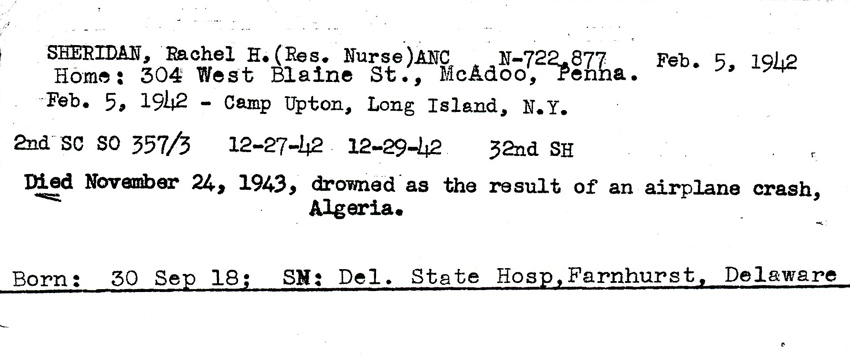

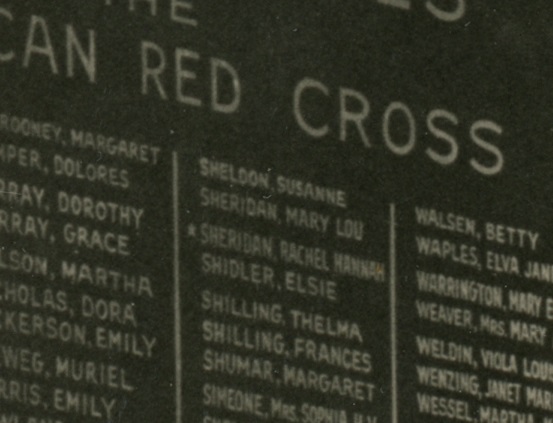

She graduated from McAdoo High School in 1936. In the fall of 1938, she began nursing school at the Delaware State Hospital in Farnhurst, Delaware. She graduated in 1941. Like many others, Sheridan was recruited for the Army Nurse Corps through the American Red Cross. 2nd Lieutenant Sheridan went on active duty in the U.S. Army on February 5, 1942, serving at the station hospital at Camp Upton, New York. Sheridan’s sister, Mary Lou Sheridan, also a graduate of nursing school at Delaware State Hospital, became a U.S. Army nurse herself. Her older brother, John, served in the U.S. Marine Corps and her younger brother, Thomas, served in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

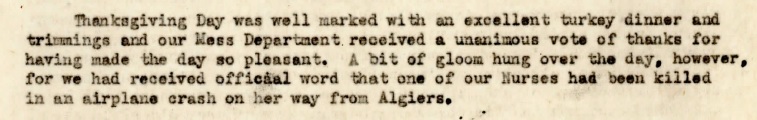

The annual reports written by Lieutenant Colonel Harold L. Goss and Principal Chief Nurse Helen W. Brammer are some of the best sources of information about the 32nd Station Hospital, but they rarely discuss individuals. Goss didn’t mention Sheridan’s death at all in his 1943 report. Brammer wrote in her 1943 nursing report only that “A bit of gloom hung over [Thanksgiving], however, for we had received official word that one of our Nurses had been killed in an airplane crash on her way from Algiers.”

The unit’s morning reports don’t offer any more useful information. The November 24, 1943, report simply stated that Sheridan’s status went “[From duty] to deceased.”

Besides the Goss and Brammer reports and unit morning reports, the best sources of information about the 32nd Station Hospital are the memoirs of Willard Havemeier and Dwight McNelly. In this particular case, the fact that they were writing decades later about events they did not witness proved problematic in piecing together Sheridan’s fate.

Willard Havemeier’s Account

Writing over half a century later, Havemeier recalled that “I became friendly with one of the nurses, Rachel Sheridan, a real Irish beauty with a great smile. We were seeing each other regularly at the dances. I really liked her a lot.”

As for what happened to her, he wrote:

The nurses also had dances at their hotel where only officers were invited. Apparently one night she met a fighter-bomber pilot, and accepted a ride in his plane. This was tantamount to going AWOL. When Rachel didn’t show up for work, an investigation was initiated, and it was discovered that she had gone off on the plane. The plane never returned, and no traces of it were ever found. The Registrar’s Office was responsible for the paper work in all deaths or missing in action cases, and it fell to us to prepare her effects for shipping home. When we received her footlocker, I was still not able to believe what had happened[…]For a long time a pall hung over our unit. Rachel was the first of us to go. We suddenly realized that our youth was not the protection we had believed it to be. I thought about Rachel for a long time. I still do.

Heartfelt as Havemeier’s memories of Sheridan are, his recollections of the circumstances of her death are not accurate. She did not in fact disappear without a trace, nor did she die taking a joy ride in a fighter-bomber.

Dwight McNelly’s Account

Dwight McNelly’s account (in his unpublished manuscript, written sometime prior to 1987 and now in the collection of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library) also has some accuracy issues, though it perhaps gets closer to the truth than Havemeier’s account.

As the war progressed, and more passes were now being given to the Officers, we felt that victory would soon be ours in N. Africa. A tragic event unfolded! A group of nurses were scheduled to go to the rest area near Algiers. We were happy for them.

The location McNelly gave for the nurses’ leave is puzzling given that Chief Nurse Brammer’s nursing report listed the usual nurse R&R locations Béni Saf and Ain el-Turck. Both were close to Oran, as opposed to Algiers, which was located hundreds of miles away.

McNelly recalled that after word got out that a nurse had been killed:

Because of little knowledge of just which nurses had actually gone from our unit, we were perplexed as to the young nurse that was reported killed. We didn’t have that many younger nurses actually. It was some time before the returning nurses told us the facts and with the lectures on wearing the dog-tags and always being signed out and not on A.W.O.L….We were shocked at the story!

What happened, as McNelly recalled, was:

Most of the nurses that went on leave were in a group and soon they were asked if they were missing anyone or were there any other medical units sending their nurses to the same spot. Feeling they could offer no help, but being told that a nurse had been brought into a hospital unit and she had no identification on her, they wanted to see the body themselves. It was one of our nurses and the apparent tale was as follows: she had gone A.W.O.L., flown with an American pilot in a Piper Cub, which crashed in the surf outside Algiers…killing both. She had not worn her dog-tags..We named the chapel after her at this time and of course the chaplain had the duty of writing the next-of-kin “killed in action”.

(Six minor typos corrected for clarity purposes.)

Some aspects of McNelly’s account are more accurate than Havemeier’s. Sheridan was indeed killed in a crash at sea near Algiers and did not vanish without a trace. Her Individual Deceased Personnel File (I.D.P.F.) confirms that she was not wearing her dog tags when she died.

Other parts of the McNelly’s account are problematic. The part about her going A.W.O.L with an American pilot and crashing in a Piper Cub sounds rather similar to Havemeier’s account and may accurately reflect the rumors going around the unit after the crash. However, the aircraft she was riding in with neither a Cub nor a fighter-bomber, but a transport aircraft. (Havemeier was in contact with McNelly after the war, so one man’s recollections may have influenced the other’s.) Unit records also make it clear that 32nd Station Hospital nurses went to rest camps close to Tlemcen and accessible by ground transportation. Indeed, only Principal Chief Nurse Helen W. Brammer is documented to have traveled to Algiers on official business. Sheridan’s I.D.P.F. also indicates that her body was identified by Captain S.H. “Bud” Dryden, a flight surgeon with the 64th Troop Carrier Group, not by anyone from the 32nd Station Hospital.

As a sidebar, McNelly mentioned that Sheridan was one of the younger nurses in the unit. Sheridan was 24 when she went overseas, and 18 of the original 55 nurses (about 1/3) were 24 or younger. When the nurses joined the unit, their median age was 26 and their average age was 28; the youngest was 21 and the oldest was 43. At that time, 37 of the 55 (about 2/3) of the nurses were in their 20s, so McNelly’s statement that “We didn’t have that many younger nurses actually” is a little inaccurate.

Missing Air Crew Report

In fact, the aircraft involved in the crash that claimed Lieutenant Sheridan’s life was neither a fighter-bomber nor a Cub, but rather a Douglas C-47, the U.S. military’s transport workhorse of the era. I was surprised to find out that an anonymous researcher had already done the most important legwork for me when he recorded details in Sheridan’s Find a Grave entry. The researcher even provided the serial number on the C-47, 41-7811. With that in hand, it was an easy matter to track down details of the crash on the Aircraft Safety Network website, and the more detailed Missing Air Crew Report (M.A.C.R.) at the National Archives.

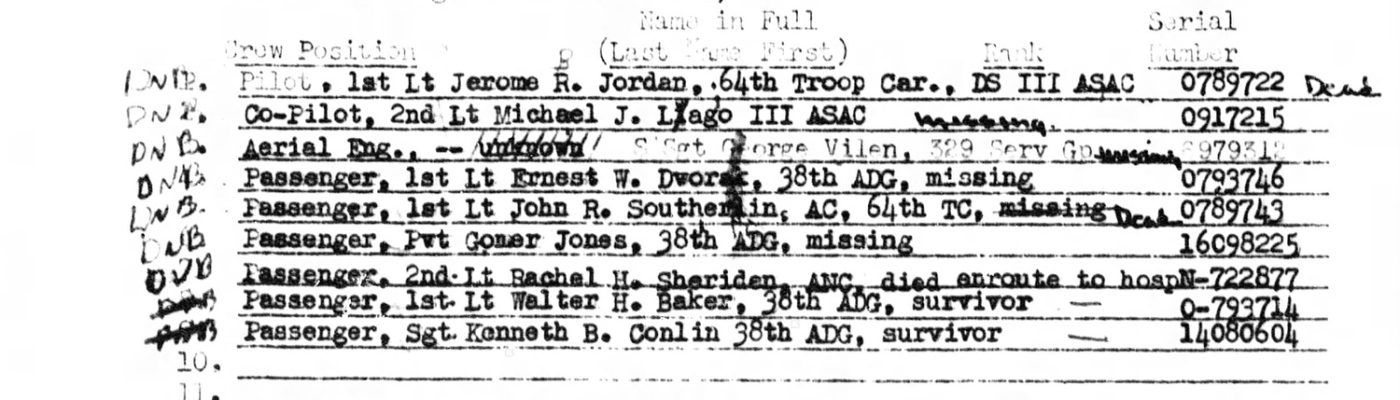

According to the M.A.C.R., on the morning of November 24, 1943, 2nd Lieutenant Sheridan was aboard a C-47 en route from Maison Blanche (Algiers) to La Sénia (Oran). There were three crew members and a total of six passengers on board.

The plane’s crew consisted of:

- Pilot: 1st Lieutenant Jerome B. Jordan, Jr. (16th Troop Carrier Squadron, 64th Troop Carrier Group, on detached service with III Air Service Area Command)

- Co-Pilot: 1st Lieutenant Michael J. Lagio (Headquarters Squadron, III Air Service Area Command)

- Aerial Engineer: Staff Sergeant George Vilen (42nd Air Service Squadron, 329th Air Service Group)

The passengers were:

- 1st Lieutenant Ernest W. Dvorak (Repair Squadron, 38th Air Depot Group)

- 1st Lieutenant John R. Southerlin (16th Troop Carrier Squadron, 64th Troop Carrier Group)

- Private Gomer Jones (38th Air Depot Group)

- 2nd Lieutenant Rachel H. Sheridan (32nd Station Hospital)

- 1st Lieutenant Walter H. Baker (38th Air Depot Group)

- Sergeant Kenneth B. Conlin (38th Air Depot Group)

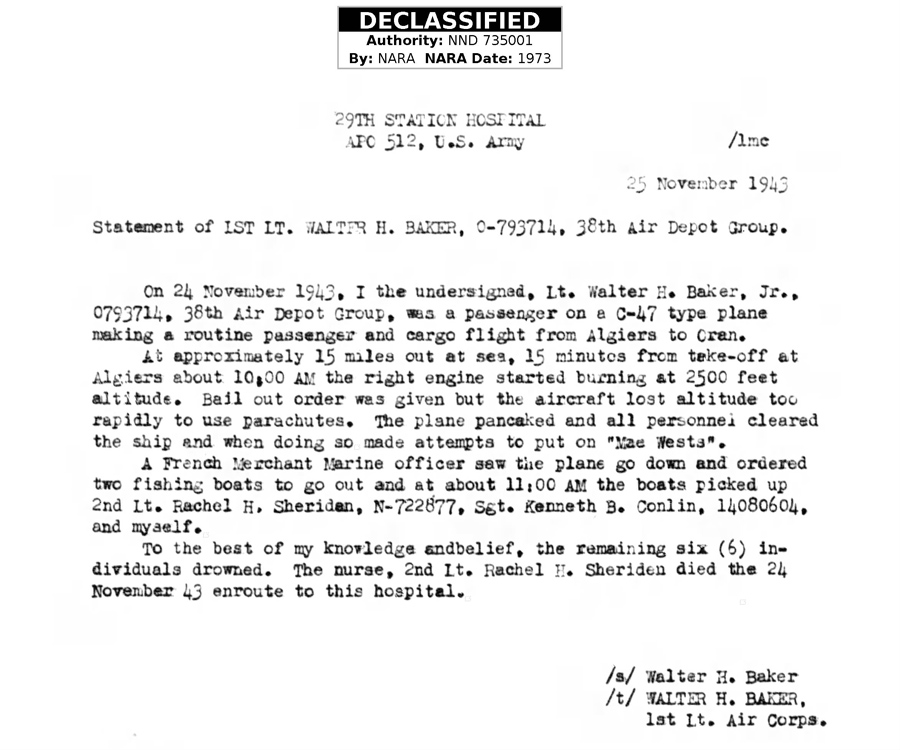

Two of the passengers lived to tell the tale: 1st Lieutenant Walter H. Baker and Sergeant Kenneth B. Conlin. Both submitted statements that were identical, word for word, so it’s not clear who actually wrote them. The statements were dated November 25, 1943, and submitted from the 29th Station Hospital (located in Algiers at the time). The statements answer many but not all questions about Lieutenant Sheridan’s fate.

The text of Baker’s statement is as follows (although the paragraphs can’t be formatted the same way as the original report displayed below due to limitations with web display):

On 24 November 1943, I the undersigned, Lt. Walter H. Baker, Jr., 0793714, 38th Air Depot Group, was a passenger on a C-47 type plane making a routine passenger and cargo flight from Algiers to Oran.

At approximately 15 miles out at sea, 15 minutes from take-off at Algiers about 10:00 AM the right engine started burning at 2500 feet altitude. Bail out order was given but the aircraft lost altitude too rapidly to use parachutes. The plane pancaked and all personnel cleared the ship and when doing so made attempts to put on “Mae Wests” [life vests].

A French Merchant Marine officer saw the plane go down and ordered two fishing boats to go out and at about 11:00 AM the boats picked up 2nd Lt. Rachel H. Sheridan, N-722877, Sgt. Kenneth B. Conlin, 14080604, and myself.

To the best of my knowledge andbelief [sic], the remaining six (6) individuals drowned. The nurse, 2nd Lt. Rachel H. Sheriden [sic] died the 24 November 43 enroute to this hospital.

The statement implied that all of the passengers and crew survived the crash and none were trapped when the plane sank, but the fact that they “made attempts” to get their life vests suggested that some or all of them were unsuccessful. At any rate, six of the people on board the aircraft disappeared in the roughly one hour it took the rescue boats to arrive.

A memo in the report dated about one month later (it looks like December 21, 1943) states: “The two survivors are on this day present on a full duty status at proper station.” That suggests that neither Baker nor Conlin were severely injured in the crash. That made me wonder how Sheridan died.

If her death was indeed en route to the hospital, that would tend to rule out drowning. Did Sheridan suffer mortal injuries in the crash or die of hypothermia? I don’t have data on late November water temperatures in the Mediterranean Sea from the 1940s, but modern records suggest that water temperatures in that part of the sea would be in the upper 60s (Fahrenheit) at that time of the year, which for most people would be survivable for at least two hours.

Sheridan’s Personnel File

Like most of the U.S. Army’s World War II-era personnel files, Sheridan’s was destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. An inquiry about her file resulted only in a “reconstructed” file which revealed little additional information:

Interestingly, the file stated that she drowned following the crash. If accurate, that would suggest that either the Missing Air Crew Report was incorrect, or the statement that she died during transport to the hospital would be better understood as being when the rescuers determined she was beyond saving. This sort of discrepancy is not uncommon even today, when a newspaper report may state that a victim died at the hospital, when that is merely where they were pronounced dead (after resuscitation attempts were abandoned).

While taking another look at the evidence in January 2022, I located a digitized hospital admission card under Sheridan’s service number. It also stated that she drowned following a plane crash. (Hospital admission cards were filled out even when someone died prior to reaching treatment.) A hospital admission card stated that Conlin was treated for exposure. I was unable to locate a card for Baker.

Absent Without Leave?

The M.A.C.R. clears up quite a few mysteries about the crash itself, but does nothing to explain how Sheridan ended up on the ill-fated aircraft in the first place. If she was in Algiers with other nurses on leave as McNelly claimed, the idea that she was A.W.O.L would be nonsense. On the other hand, the usual nurses’ R&R locations were Béni Saf and Ain el-Turck, neither of which required a plane to get to. It was clear that Sheridan was identified the same day since her death was recorded in the unit’s morning report for the period ending at midnight that night. If news had been delayed, it would probably have been recorded on a future morning report with the event backdated. That word arrived so quickly may indicate that Sheridan relayed her unit to the other survivors prior to her death, that it was recorded on a passenger manifest left behind at Maison Blanche, or that the person who identified her body knew her unit.

An article entitled “Lt. Rachel Sheridan, McAdoo Army Nurse, Dies in Africa,” printed in The Plain Speaker (Hazleton, Pennsylvania) on December 16, 1943, reported: “She has been overseas since January, 1943 and only last Saturday her mother had received a letter dated November 18 in which she said she was in good health, enjoying life in Africa and that she had a ride in an airplane a few days previous.”

The fact that her last letter mentioned an airplane ride is an intriguing detail. It suggests that there was truth in the McNelly and Havemeier tales that she went joyriding in an airplane, even if the details they recounted (the kind of aircraft, that she met the pilot at a party, and likely the part about nurses being on leave in Algiers) were suspect.

Although I hesitate to draw too many conclusions based on the handful of surviving documents, my impression is that most members of the 32nd Station Hospital traveled by ground motor transport or train while on official business in Algeria. Sheridan, however, had flown at least twice in the span of maybe two weeks. Air travel was a novelty back then, and it was probably not difficult for a nurse to talk air crew into letting them hitch a ride when there was space available.

Dr. Lowell E. Vinsant’s Account

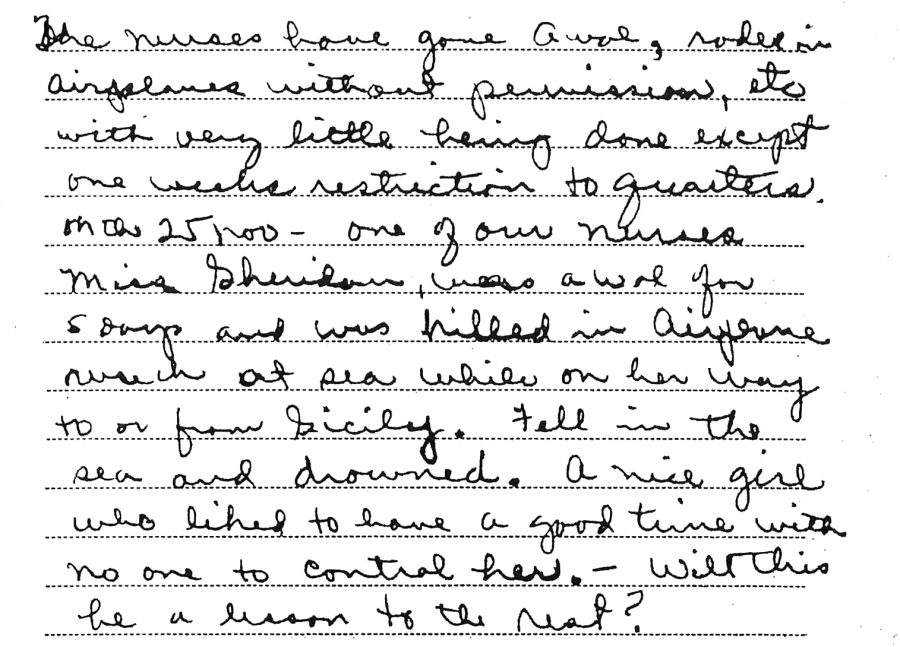

Did Sheridan simply enjoy flying, and decide to try to get aboard an aircraft again when off duty? Several months into my search for details about her fate, in March 2019, the daughter of Dr. Lowell E. Vinsant sent me a copy of her father’s World War II journal. An entry dated November 27, 1943, suggested that joyriding in aircraft was something of a pastime for the 32nd Station Hospital’s nurses:

The nurses have gone Awol, [rode/riden?] in airplanes without permission, etc with very little being done except one weeks restriction to quarters. On the 25 nov– one of our nurses Miss Sheridan, was awol for 5 days and was killed in airplane wreck at sea while on her way to or from Sicily. Fell in the sea and drowned. A nice girl who liked to have a good time with no one to control her.– Will this be a lesson to the rest?

Although the date of the crash listed in Dr. Vinsant’s account was one day off (and the part about Sicily isn’t correct unless she made it that far on a previous flight), it does represent a contemporary account, without the influence of memory on the accounts written years later by McNelly and Havemeier.

Interestingly enough, despite Lieutenant Colonel Goss’s reputation for being strict, Dr. Vinsant’s account implied that 32nd Station Hospital nurses regularly went for joyrides in aircraft in part because the punishment for being caught was quite light. A 1972 interview of Dr. Lee D. Cady of the 21st General Hospital—which was also operating in North Africa around the same time—provides one possible explanation:

While we were in Algeria, rather than go to headquarters to get permission to give my officers and nurses regulation orders, I’d give them passes [for whatever] they were planning to do. My passes were irregular in that I wasn’t too specific about where they were going, how they were going, or anything except that they had so many days. In this way I was developing quite an intelligence system. My nurses would travel every place – Cairo, Gibraltar, and so on. One of them came in and said, “I know where we’re going. We’re going to Italy next and we’re going to put up in a fairgrounds.” I said, “How do you know?” [She said] “General So-and-so told me so.”

Oddly enough, Dr. Vinsant’s wrote that Sheridan was A.W.O.L. for five days. Elsewhere in his journal, Dr. Vinsant mentioned that it wasn’t uncommon for a member of the hospital to take off briefly (presumably hours, not days), as long as they got someone to cover them. Alice Griffin’s letters also indicated that aside from leave and visits to rest camps, nurses did have occasional days off. Regardless of whether infractions like brief absences from duty or joyriding aircraft while off duty were generally treated laxly by the hospital’s leadership, it seems unlikely that a nurse being absent for two or more days would have been overlooked. It is also not supported by the unit’s morning reports, which changed her status “[From duty] to deceased.”

To answer Dr. Vinsant’s rhetorical question, some nurses evidently continued to enjoy flying even after Sheridan’s death, judging by a photograph from Ruby Milligan’s photo album taken in 1944 or 1945. Milligan apparently flew with three other nurses aboard a B-25 Mitchell, captioning one of the photos from the adventure: “Forbidden plane trip!”

The Survivors

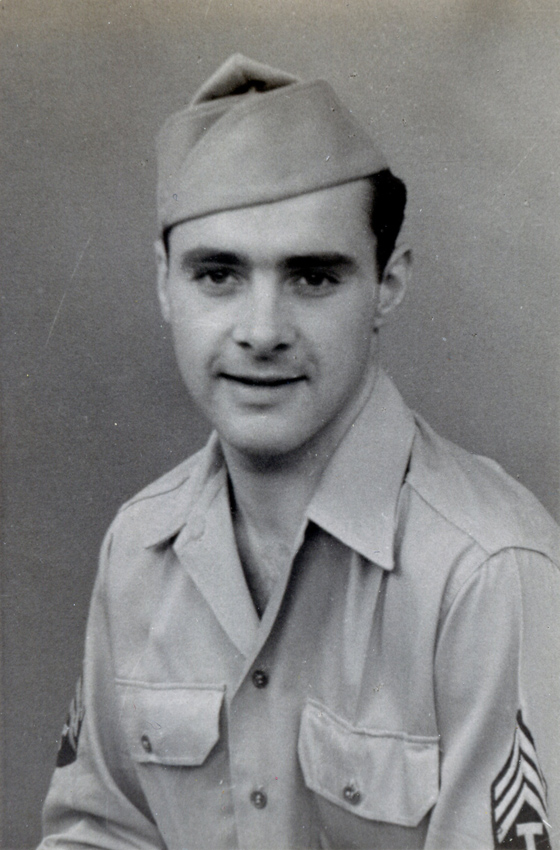

The M.A.C.R. listed 1st Lieutenant Walter H. Baker’s father’s name (also Walter H. Baker) and address, 2015 Valentine Avenue in New York City. I found a draft card for the elder Baker listing his name as Walter Hewlett Baker. The 1930 census listed two Walter H. Bakers living on Valentine Avenue; the younger Baker was 11 years old at the time. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Walter H. Baker, Jr. (service number 12053264) enlisted as an aviation cadet on January 17, 1942. Aviation cadets who were commissioned after completing training as a pilot, bombardier, or navigator were issued a new officer service number.

Those details match Lieutenant Colonel Walter H. Baker, Jr. (March 4, 1919 – February 13, 1981), who is buried in Poughkeepsie, New York. His headstone indicates that he was a U.S. Air Force veteran of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. His obituary (printed in the Ithaca Journal on February 14, 1981) stated that “U.S. Air Force Col. Walter Hewlett Baker Jr. (Ret.), 61, of Locke Road, Groton, died Friday, Feb. 13, 1981, in Veterans Administration Hospital, Syracuse, after a long illness.” The obituary also stated: “Col. Baker retired from the Air Force in 1969 after 29 years of service. During World War II, he was a bomber pilot and was shot down twice. He served in the North African, Italian and French campaigns.”

It is likely, but not confirmed, that one of the two crashes that he survived was the C-47 incident. Baker’s obituary listed his wife Lucille Stoeppler Baker (1919–2010) as a survivor, but no children.

Sergeant Kenneth B. Conlin, Jr. (November 9, 1919 – October 2, 2015) was born in New York City, but as a child he moved with his family to St. Petersburg, Florida. Conlin returned there after the war and eventually took over running the family business, the Lighthouse Restaurant. He later opened another restaurant, Ken’s Original Wine House. Conlin married Jean R. Thom, with whom he raised four children. He died in Williston, Florida, aged 95. The plane crash was a prominent enough event in his life that his obituary mentioned it, stating that “he was shot down while ferrying a C47 military plane from North Africa to Italy.”

A Friendly Fire Incident?

On June 4, 2019, a little over a month after this article was first published, I was contacted by David Procaccini, who has been researching the 38th Depot Repair Squadron for years. He wrote me:

I am familiar with the Rachel Sheridan crash. I spoke to Ken Conlin who refused to go into detail about the crash and Walter Baker’s widow and other members of the 38th and they all alluded to the C-47 in which they were flying being shot down by friendly fire. Baker’s wife was emphatic about it.

In a phone conversation the following day, he mentioned that while Conlin discussed other matters freely, when Procaccini broached the topic of the crash, Conlin ended the interview. Procaccini was suspicious about the fact, noted above, that both survivors’ statements were identical, perhaps suggesting that a third party wrote both. He speculated that if the M.A.C.R. did have statements that whitewashed the cause of the crash, it might have been because it was mere months after another embarrassing friendly fire incident in which aircraft carrying U.S. paratroopers were shot down during Operation Husky.

The possibility that the crash was caused by friendly fire is both intriguing and heartbreaking. It should be noted that the statements about the crash being due to friendly fire did not come from directly from either of the survivors. Furthermore, as the Havemeier and McNelly accounts about the crash indicate, it is quite possible for rumor to obscure the truth, especially when the events were not directly witnessed by those recounting the story later.

Conlin’s refusal to discuss the crash doesn’t necessarily support nor refute the friendly fire allegation. His behavior could be interpreted as either reluctance to relieve traumatic memories of an event that he narrowly escaped with his life, unwillingness to shed light on an event that was officially covered up, or both. Still, if the crash was indeed the result of friendly fire, it would explain why both Conlin’s and Baker’s obituaries stated that the plane was “shot down.” In that context, the wording would not be mere error or embellishment, but rather an accurate description of the event.

Major Paul J. Collins, who was a bombardier and navigator in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, reviewed my research during the summer of 2020. Given that he was with the Eighth Air Force in the European Theater during 1944 rather than the Mediterranean in 1943, he could only evaluate it within the context of his own knowledge and experiences. He told me during a pair of interviews on July 13, 2020, and November 20, 2020, that he was surprised at the official account, because the C-47 was the “most reliable plane ever built” and one suffering an engine fire was “highly unusual.”

Major Collins said that friendly fire incidents did occur during World War II, even in broad daylight, though based on available information, it was impossible to say whether the Sheridan incident was an instance of fratricide. “I’m not saying it happened. I don’t know,” Collins said. “It was known to happen. There were instances of friendly fire bringing down our planes.”

I also asked Brigadier General Kennard R. Wiggins (Delaware Air National Guard, retired, curator of the Delaware Military Museum) for his take on the various accounts of the accident. He cautioned me that “I am not a rated aviator, nor a flying safety expert. I speak as a historian, and an Air Force veteran, but not with subject matter expertise.” That being said, he said that though the friendly fire theory could not be ruled out, he was skeptical of it. General Wiggins pointed out that “The C-47 is a pretty recognizable airplane. If it was daylight, and near its base, it is hard to imagine an accidental misidentification.” A more mundane reason General Wiggins suggested, that could explain both the engine fire and why the survivor refused to talk about the crash was that it “may have touched a nerve on an embarrassing maintenance failure, or possibly some ‘pilot error’ oversight that was swept under the rug.”

John W. Holmes Account

On November 2, 2020, David Procaccini pointed me to a memoir by John W. Holmes. Holmes was a navigator in the 16th Troop Carrier Squadron, 64th Troop Carrier Group. That was the same unit as 1st Lieutenant Jerome B. Jordan, the ill-fated C-47’s pilot. Holmes recalled:

On the trip back [from Libya to Tunis], we had a load of pilots and ground personnel. We flew mostly at sea, and about 150 miles from Tunis, we had landfall and Jordan, the 1st pilot descended to 150-200′ and buzzed anything in sight, scattering livestock all around the farms and villages, and scaring the Arabs. The P-38 pilots and I were alarmed, and the fighter pilots remarked that they’d not do that. Even back then, the Arabs had reasons for not liking us. After all, we were fighting Hitler who hated Jews as Arabs do, however perhaps for different reasons.

Jordan died later in 1943. He and a good friend of Jim Lowry’s, Johnny Southerland, were flying along the North African coast and had to crash land ten miles off the coast of Algiers, Algeria. The water was very rough –they had very little chance of surviving. Everyone on board was killed, except for a flight nurse, who was rescued, and escaped death with just a broken leg. Jordan’s nickname was “Mo,” but his real name was Jerome Bascom Jordan. He was from Georgia and went through pilot training (Class of 42E) with another 16th TCS pilot, Jim Lowry.

Jordan caught in soft ball games in the Tunisian desert and I played shortstop. There was a line of cacti out in the outfield area. He introduced me to the fruit, and the quills were something else.

In the first passage, Holmes implied that Lieutenant Jordan flew recklessly on at least one flight, though there’s no evidence that pilot error caused the crash on November 24, 1943. Indeed, if Holmes was right about weather conditions that day, the fact that there were any survivors at all may be attributable to the pilots’ skill in ditching the C-47. Of course, the second paragraph should be taken with a grain of salt since Holmes did not witness the accident. In his telling, Sheridan was a flight nurse, and the crash’s only survivor.

Individual Deceased Personnel File (I.D.P.F.)

On February 25, 2020, I made a Freedom of Information Act request for Sheridan’s I.D.P.F. from the U.S. Army Human Resources Command at Fort Knox, Kentucky. I received a copy of the document in the mail on November 2, 2020.

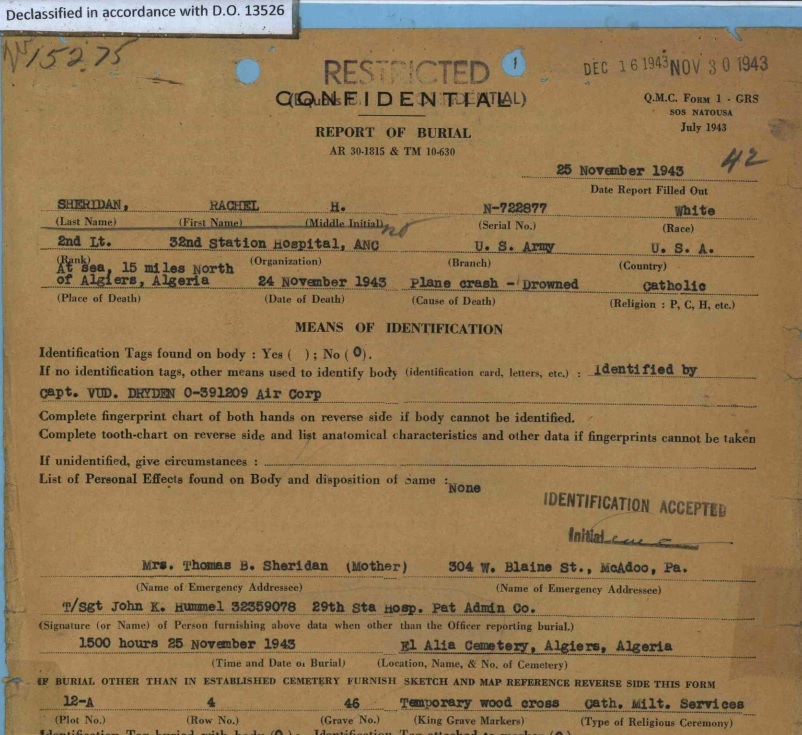

The file, though interesting, provided only a few new pieces of information. Perhaps the most important was a copy of the Report of Burial from November 25, 1943. This document gave her cause of death as “Plane crash – Drowned” and stated that she was initially buried at El Alia Cemetery in Algiers. Perhaps the most interesting section pertained to how she was identified. Just as Dwight McNelly’s manuscript had claimed, Sheridan was not wearing her dog tags at the time of her death. The document stated she was “identified by Capt. VUD. DRYDEN O-391209 Air Corp”. David Procaccini pointed out that Dr. Sam H. “Bud” Dryden (1914–2002) was a 64th Troop Carrier Group flight surgeon and that “VUD” was probably a typo. A December 20, 1943, article in The Abilene Reporter-News (Abilene, Texas) reported Dr. Dryden’s recent promotion to major, adding:

Major Dryden, now in Sicily, has been overseas since August, 1942. He entered the army in June, 1941, immediately after finishing his internship in Fort Worth City-County hospital. He was graduated at Baylor medical school in Dallas after two years pre-medical work in Abilene Christian college.

An October 16, 1944, article in the same paper stated that he “was aboard one of the troop-carrying and glider-towing planes that spearhead[ed] the assault on the southern coasts of France [during the beginning of Operation Dragoon], August 15.” (The article didn’t state that Major Dryden parachuted or otherwise joined the airborne operation on the ground.)

How Dr. Dryden came to identify Sheridan is a minor mystery in of itself. Dr. Dryden, like the pilot of the ill-fated C-47, was a member of the 64th Troop Carrier Group. I can only speculate as to how he and Sheridan knew one another. As medical personnel, had they met previously in a professional capacity (like if Dr. Dryden had accompanied a patient to the 32nd Station Hospital)? Or had he been a passenger aboard her outbound flight from Oran to Algiers? As it turned out, an account of the incident provided by Sheridan’s family soon after the I.D.P.F. arrived may offer a clue.

Sheridan Family Accounts

On November 4, 2020, I was finally able to locate and contact descendants of one of Lieutenant Sheridan’s brothers. The following day, I spoke with 2nd Lieutenant Sheridan’s niece, Rachel McHugh. Like her namesake, McHugh became a nurse. She told me of one story passed down through the family, that three of the four Sheridan siblings who served in World War II were able to meet in New York City before Lieutenant Sheridan went overseas. Present were Lieutenant Sheridan, Mary Lou Sheridan (later Bauer, 1922–1997) who joined the Army Nurse Corps on May 15, 1943, and Thomas T. Sheridan, Jr. (1924–2002), who joined the U.S. Navy on June 30, 1943. A fourth sibling who served, John T. Sheridan (1913–1984), was either already overseas or about to ship out with the U.S. Marine Corps. The visit must have been sometime in 1942 or early January 1943, though it’s unclear if it occurred while Lieutenant Sheridan was assigned to the hospital at Camp Upton (located on Long Island) or with the 32nd Station Hospital at Camp Kilmer. It was the last time Mary Lou and Thomas saw their sister.

I also spoke at length with Lieutenant Sheridan’s great-nephew, Leo McHugh. He told me that Sheridan was a personal hero, helping inspire him to become a critical care flight paramedic.

In an email the following day (written before he read my article, to avoid influencing his memories), Leo McHugh recounted what his grandmother—Lieutenant Sheridan’s sister-in-law—told him about the crash. According to McHugh’s grandmother, Rachel was in a relationship with a major in another unit.

She continued, Rachel saw an opportunity to meet him [and] volunteered for a transport, taking wounded back to a larger hospital. It was on this transport that the plane crashed. I can remember her saying that it was a mechanical issue which resulted in the plane crash.

She told me the plane crashed into water. Following the crash, Rachel was rescued by Merchant Marines, in addition to one other person. However, Rachel died while in an ambulance, being transported to a hospital. She told me everyone died but one person, and the plane was never recovered. My grandmother didn’t know the name (or [did] not remember) of the Major, Rachel was going to see. However, I do remember her telling me that he was a pilot. Any additional detail beyond that, I simply cannot remember.

That Sheridan was dating a pilot is consistent with the Havemeier and McNelly accounts. The details of the crash in this account are also generally consistent with those of the survivors’ statements. Since the crash returned on the return leg (and there’s no indication that any of the passengers on the C-47 that crashed were patients), if Lieutenant Sheridan was accompanying patients, it would have had to have been on the outbound flight from Oran to Algiers. It would be curious that Sheridan would be picked for that assignment, since the U.S. Army Air Forces had flight nurses (the first of whom graduated on February 18, 1943) to accompany patients on medical evacuation flights.

It’s plausible that if a flight nurse was unavailable, military necessity would dictate that a ground nurse be assigned to accompany a patient transport. The only instance I’ve come across so far where a nurse acted in that capacity during World War II is when 1st Lieutenant Bernice M. Wilbur (head U.S. Army nurse in the North African Theater of Operations) cared for Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair (head of Army Ground Forces) during an evacuation flight back to the United States after he was wounded in Tunisia on April 23, 1943. However, I have not come across any other records or stories that suggest any other 32nd Station Hospital nurse was ever pressed into duty as a flight nurse. For that reason, I think it likely that whoever told the Sheridan family about the crash may have embellished that detail to gloss over that Lieutenant Sheridan may have been on the flight without authorization from her commanding officer.

This version of the story suggests a possible explanation for how Dr. “Bud” Dryden, a flight surgeon with the 64th Troop Carrier Group, came to identify her body. He certainly could have been familiar with Lieutenant Sheridan if she was involved in air medical transport or dating an officer in his unit.

Conclusions

2nd Lieutenant Sheridan was initially buried after a Catholic military service in the El Alia Cemetery in Algiers on November 25, 1943. After the war, in September 1947, the Army offered her family the option of having Sheridan’s body returned home or laid to rest in a permanent military cemetery in North Africa. After considerable debate within the family, Lieutenant Sheridan’s mother requested that her body remain abroad. On February 8, 1949, Sheridan’s body was laid to rest at the U.S. Military Cemetery Tunis (Carthage), Tunisia, now known as the North African American Cemetery. The six men killed in the crash are also memorialized on a cenotaph there, though their bodies were not recovered. Sheridan’s mother also placed a memorial honoring her daughter at Sky-View Memorial Park in Hometown, Pennsylvania.

This inquiry illustrates the challenges inherent in trying to piece together the details of an incident 75 years after the fact. Although there are no longer any living witnesses, the handful of reports and accounts do paint a partial picture of the events leading to 2nd Lieutenant Sheridan’s death. Based on the available evidence, it seems likely if not proven that Sheridan ended up on the ill-fated fight while joyriding on an aircraft, a practice that, though unauthorized, was considered a minor infraction.

In terms of the cause of the crash, I consider the friendly fire explanation to be plausible, but I share General Wiggins’s skepticism that it actually occurred. The various stories of the incident that I’ve obtained so far all seem to have a degree of truth to them, but also plenty of inaccuracies.

I agree that there are some odd things about the M.A.C.R. There are two major questions that raises. First, was there was a coverup by military authorities? Certainly, they were more than capable of keeping a lid on discouraging news. The friendly fire incident during Operation Husky didn’t become public for nearly a year, despite the loss of 23 aircraft with over 300 casualties. In contrast, the Sheridan incident was a single plane with seven fatalities. Given that the M.A.C.R. was going to be confidential anyway, would authorities have even bothered to coerce the survivors into writing (or going along with) false statements? The second question is, in the event that there was indeed a coverup, what exactly were they hiding? Was it friendly fire, pilot error, maintenance error, or some other reason I haven’t considered?

The Operation Husky incident occurred at night when gunners aboard Allied ships (which had been attacked by German twin-engine aircraft just minutes before) mistook friendly aircraft for another wave of enemy aircraft. In the Sheridan incident, the C-47 was about 10 miles offshore, which would tend to rule out anti-aircraft fire, as land-based guns wouldn’t have the range. There was no indication that Allied warships were present—at the very least, the rescue was performed by civilian vessels. That means that if friendly fire did occur, an Allied fighter would be the most likely culprit. For that to happen, the fighter pilot would have to—in broad daylight and unlimited visibility—misidentify a C-47 that was flying just 15–20 miles from a major Air Transport Command base along a standard east-west route used by numerous cargo plane flights every day. Though friendly fire would certainly not be impossible, it seems rather unlikely under those conditions.

The other reasons for hushing up the incident are plausible, but unsubstantiated. An anecdote established that 1st Lieutenant Jordan flew recklessly at least once. Admittedly, that raised a question in my mind whether he somehow caused the engine fire by pushing the engines too hard after takeoff. However, there is no evidence to suggest that occurred (or that the survivors, who were passengers rather than flight crew, would have known if it did). It seems a little unfair to raise the possibility of pilot error at all, considering that if not for the pilots’ skill in ditching the aircraft, there would have been no survivors from the crash at all. And, although maintenance errors undoubtedly occurred during the war just as they do now, there is no specific evidence to suggest that one caused the engine fire.

Despite some reservations, in the absence of convincing evidence to the contrary, I believe the most likely cause of the crash to be exactly what the Missing Air Crew Report stated: “Fire of unknown origin in right engine forced plane down at sea[.]”

I am hopeful that additional contemporary accounts or documents will eventually turn up, which may answer some of the remaining questions about Sheridan. If additional information comes to light, I will update this article accordingly.

Last updated October 20, 2023

[…] Author’s note: Sheridan served in my grandfather’s unit. This article incorporates some text from my previous articles published to my 32nd Station Hospital website, “Nurses of the 32nd Station Hospital: Part III (Last Names N–S)” and “The Mystery of Rachel H. Sheridan, the 32nd Station Hospital’s Lost Nurse.” […]

LikeLike